Execution

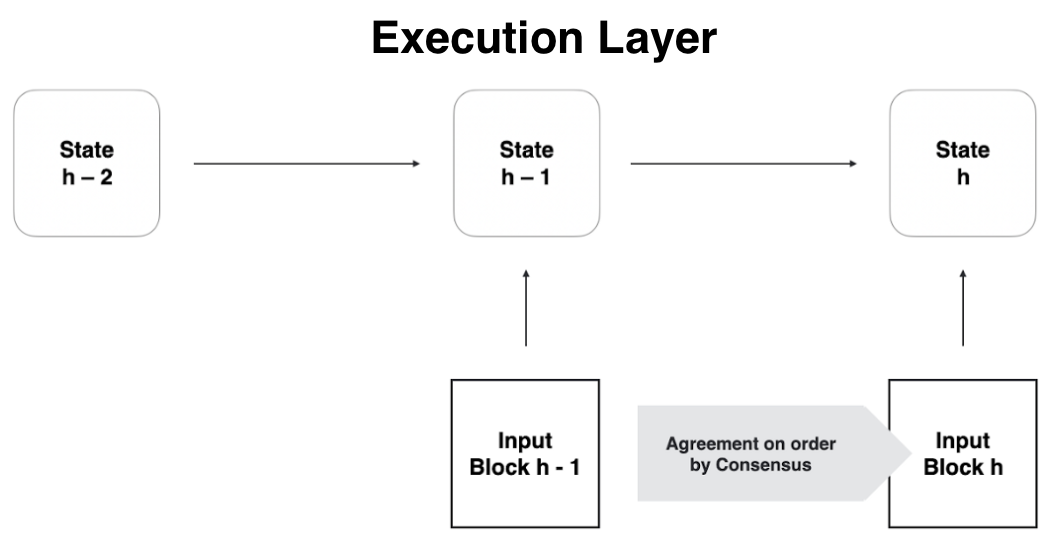

The execution layer is the topmost layer of the BIG core stack. It deterministically schedules and executes the messages that have been agreed upon by consensus and inducted into the cube queues by message routing, thereby changing the state of the subnet in a deterministic manner across all nodes. Executing the same sequence of messages on every node in the subnet ensures that the same final state is achieved on each node at the end of the round.

A cube smart contract on BIG consists of WebAssembly (Wasm) bytecode, representing the smart contract program, and a set of memory pages representing its state. The Wasm bytecode can be modified by installing or updating the cube, while the smart contract state is modified during the execution of messages on the cube smart contract. Both the bytecode and the memory pages (i.e., the state) of the cube are maintained by every node machine in the subnet where the cube is installed. Each node in the subnet holds the same cube state and ensures that state transitions occur uniformly across all nodes in every round. This is the foundation of a replicated state machine, which is crucial to the security and resilience properties that make blockchains unique.

Replicated Message Execution

Replicated execution in BIG proceeds in rounds. During each round, the message routing layer invokes the execution layer to process (a subset of) the messages in the cube input queues. Depending on the computational effort (CPU cycles) required to execute the messages, a round may end with all messages being processed, or with the cycle limit being reached, leaving some messages for future rounds.

Each message execution can lead to modifications in the cube's state memory pages (referred to as "dirty" in operating systems terminology), the creation of new messages to other cubes within the same or different subnets, or the generation of a response in the case of an ingress message. Changes to memory pages are tracked, and the corresponding pages are flagged as "dirty" so they can be processed during state certification.

When message execution results in a new cube message targeted at another cube within the local subnet, the message can be directly queued by the execution layer into the input queue of the target cube and scheduled for execution in the same or a subsequent round. This message does not need to go through consensus since its generation and enqueuing are deterministic, ensuring that the process happens uniformly across all nodes in the subnet.

New messages targeted at other subnets are placed into the cross-subnet queue (XNet queue) and are certified by the subnet at the end of the round as part of the per-round state certification. The receiving subnet can verify that the XNet messages are authenticated by validating the signature with the originating subnet's public key.

The execution layer is designed to execute multiple cubes concurrently on different CPU cores. This is possible because each cube has its own isolated state, and cube communication is asynchronous. This form of concurrent execution within a subnet, combined with the ability of all BIG subnets to execute cubes concurrently, makes BIG scalable like the public cloud: BIG scales out by adding more subnets.

Non-replicated Message Execution

Non-replicated message execution, also known as queries, are operations executed by a single node and return a response synchronously, much like a regular function invocation in an imperative programming language. The key difference between queries and update calls is that queries cannot change the replicated state of the subnet, while update calls can. As the name suggests, queries are essentially read operations performed on one replica of the subnet, with the associated risk that a compromised replica could return an arbitrary result.

Similar to update calls, queries are executed concurrently by multiple threads on a node. However, because queries are not executed in a replicated manner, all the nodes of the subnet can concurrently execute different queries. This means that the query throughput of a subnet increases linearly with the number of nodes, whereas the performance of update calls decreases as the number of nodes increases.

Queries are similar to read operations on a local or cloud Ethereum node on the Ethereum blockchain. A dapp should use queries for non-critical operations only. For critical information, such as financial data that influences decision-making, update calls should be used to obtain the information, as the response of an update call is certified by the subnet with a BLS threshold signature and can be verified using the subnet's public key.

Deterministic Time Slicing

Each execution round progresses in tandem with the creation of blockchain blocks, which occurs roughly once every second. This imposes a limit on how much computation can be performed in a single round, with the current limit being around 2 billion instructions given the existing node hardware.

However, BigFile can handle longer tasks that require up to 20 billion instructions, and some special tasks, like code installation, can even go up to 200 billion instructions. This is achieved using a technique called "Deterministic Time Slicing" (DTS). The idea behind DTS is to pause a lengthy task at the end of one round and continue it in the next. This allows a task to span multiple rounds without affecting the block creation rate. DTS is automatic and transparent to smart contracts, so developers don't need to write any special code to take advantage of it.

Memory Handling

Managing the cube bytecode and state (collectively referred to as memory) is one of the key responsibilities of the execution layer. The replicated state that can be held by a single subnet is not limited by the available RAM in the node machines but rather by the available SSD storage. However, the amount of RAM does impact the performance of the subnet, particularly the access latency of memory pages. This, much like in traditional computer systems, depends significantly on the access patterns of the workload.

The states obtained during cube execution are certified (i.e., digitally signed) by the state management component of message routing. Some parts of the state, including the ingress history and messages sent to other subnetworks, are certified every round. The entire state of a subnet, including the state of all cubes hosted by that subnet, is certified once during a (much longer) checkpointing interval.

Memory pages representing cube state are persisted to SSD by the execution layer, freeing cube programmers from the need to manage this process. This transparent persistence enables orthogonal persistence, simplifying smart contract implementation and reducing the total cost of ownership (TCO) for a dapp, allowing for faster go-to-market times. Programmers can maintain the full cube smart contract state in either the heap or stable memory. The key difference is that the heap is cleared during cube code updates, while stable memory remains intact, hence its name. Any state in the heap that needs to be preserved through a cube update must be transferred to stable memory before the update and restored afterward. Best practices recommend storing large cube states directly in stable memory to avoid moving large amounts of data before and after each upgrade. This also helps avoid the risk of exceeding the cycles limit during an upgrade operation.

Cycles Accounting

The execution of a cube consumes resources on the BigFile network, which are paid for with cycles. Each cube holds a local cycles account, and ensuring that the account has sufficient cycles is the responsibility of its maintainer, whether that be a developer, a group of developers, or a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO). Users never pay for sending messages to cubes on BIG, a model known as the reverse gas model, which facilitates mass adoption of BIG.

Technically, when Wasm bytecode is installed or updated on BIG, it is instrumented with code that counts the executed instructions for smart contract messages. This allows for the deterministic calculation of the exact amount of cycles to be charged for a given message. Using Wasm as the bytecode format for cubes has greatly contributed to achieving determinism, as Wasm itself is largely deterministic in execution. It is crucial that cycle charging be completely deterministic so that every node charges exactly the same amount of cycles for a given operation, maintaining the replicated state machine properties of the subnet.

The memory a cube uses, including both its Wasm code and state, must also be paid for with cycles. Similar to public cloud services, consumed storage is charged per time unit. Compared to other blockchains, storing data on BIG is very inexpensive. Additionally, networking activities such as receiving ingress messages, sending XNet messages, and making HTTPS outcalls to Web 2.0 servers are paid for in cycles by the cube.

Pricing for resources on BIG is extremely competitive. Prices for a given resource, such as executing Wasm instructions, scale with the replication factor of the subnet, i.e., the number of nodes that power the subnet.

Random Number Generation

Many applications benefit from or require a secure random number generator. However, generating random numbers in a naive way during execution would compromise determinism, as each node would generate different randomness. BIG solves this problem by providing the execution layer with access to a decentralized pseudorandom number generator called the random tape. The random tape is built using chain-key cryptography.

Every round, the subnetwork produces a fresh threshold BLS signature, which is inherently unpredictable and uniformly distributed. This signature can then be used as a seed in a cryptographic pseudorandom generator, giving cube smart contracts access to a highly efficient and secure random number source.